How storytelling became a vessel for memory, resistance, and cultural survival.

In last week’s blog, we explored how Savannah shaped Flannery O’Connor’s storytelling—its shadows, grace, and Southern cadence. This week, we turn to the Gullah Geechee people, whose stories were not written but spoken, sung, and remembered. Forbidden by law to read or write, enslaved Africans preserved their culture through oral tradition. A legacy of resistance and resilience that still echoes through the isles and along the coast of Savannah.

Below, a praise house nestled in coastal greenery and a Gullah woman weaving sweetgrass baskets offer a glimpse into the spaces and hands that have carried these stories forward.

ALT text available for all images.

Historical Context

The Gullah Geechee corridor spans the coastal regions of North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida. These were the lands where enslaved Africans were brought for their expertise in rice cultivation. Savannah played a central role in this trade. Taken from diverse West African tribes, they blended languages to communicate and preserved ancestral traditions on barrier islands. Denied literacy by law, they crafted oral stories like Br’er Rabbit. These stories were not just for entertainment, but as coded resistance. These tales used wit and trickery to challenge power, teaching survival and defiance in a world where freedom had to be imagined, not spoken.

Oration as Cultural Memory

Storytelling, ring shouts, spirituals, and folktales were crucial lifelines for the Gullah Geechee people. These forms of expression functioned as tools of survival. They also served as means of resistance and remembrance. Spirituals, characterized by swaying bodies, clapping hands, and a call-and-response format, not only set the rhythm for labor but also helped uplift spirits. Since enslavers prohibited the use of drums, fearing them as instruments of rebellion, the Gullah Geechee turned to body percussion, creating music by pounding sticks and clapping hands in an act of defiant creativity. Ring shouts evolved into sacred spaces for both movement and praise.

Songs such as “Kumbaya,” often misunderstood as simple campfire melodies, actually conveyed cries for divine assistance during times of suffering. In Gullah Geechee Heritage in the Golden Isles, authors Roberts and Holladay highlight that Congress formally recognized the Gullah Geechee people in 2017 as the originators of “Kumbaya.” Through the fusion of rhythm, language, and performance, they cultivated a resilient culture that resonates deeply through generations. Here is Rastamystic performing his rendition of Kumbaya.

That legacy of rhythm, resistance, and reclamation lives on. Next, let’s walk with Sistah Patt Gunn through the streets of Savannah, where she now guides others through the stories that were once silenced, including her own.

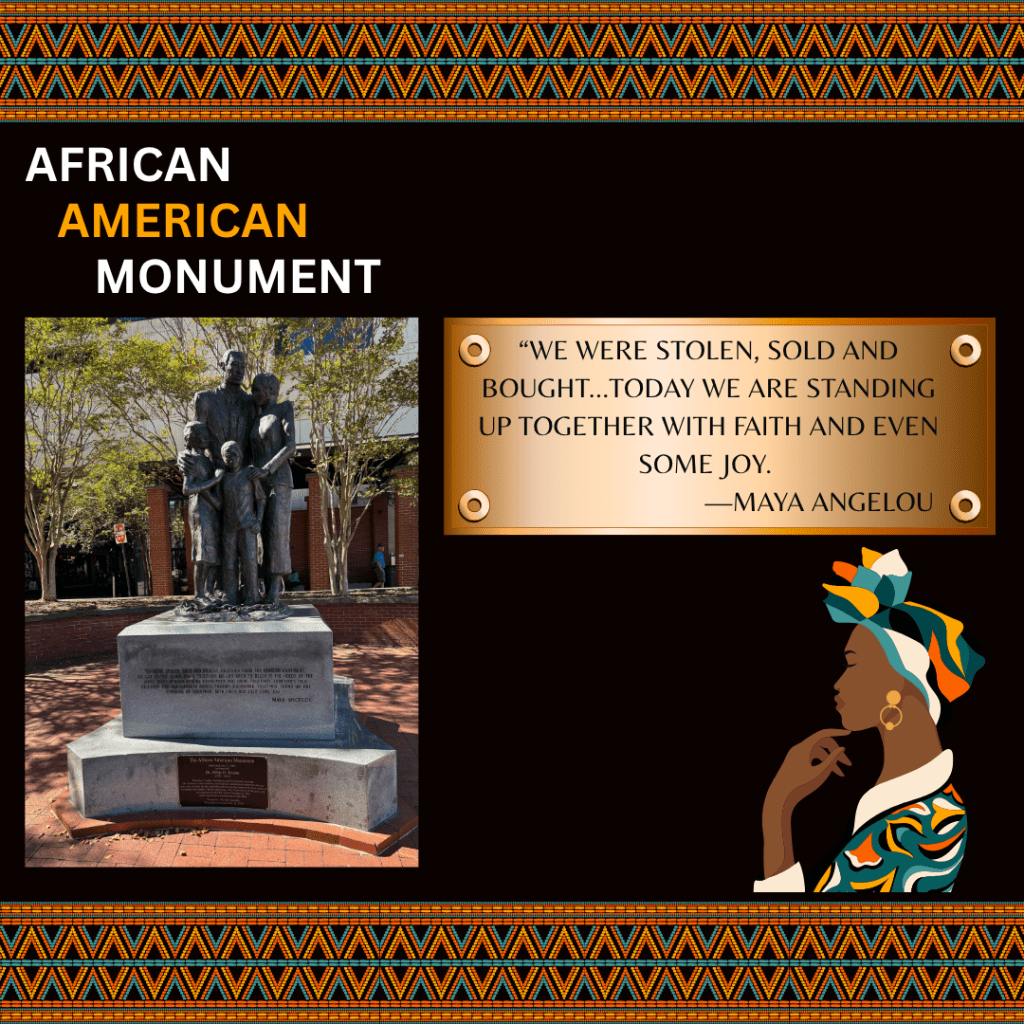

Her footsteps remind us that history isn’t just behind us, it’s beneath us, beside us, still speaking. From here, we turn to Savannah’s living landmarks, where the past lingers in bronze, stone, and belief. The African American Monument and the First African Baptist Church stand not just as historic sites, but as vessels of memory. Bearing witness to faith, struggle, and endurance.

Savannah’s Living Landmarks

Facing the Savannah River, the African American Monument stands in quiet defiance and remembrance. Its bronze figures are bound together, yet their gaze is forward, toward freedom, toward the future. The monument’s placement by the water evokes the Middle Passage and the countless lives shaped by it.

Below the sculpture is an inscription by Maya Angelou. Words that mourn, remember, and rise. You can view the full text by clicking “here” under the image above. This site doesn’t just mark history, it invites reflection, shaping Savannah’s literary voice through memory, resilience, and the enduring power of story.

On Franklin Square stands the First African Baptist Church, its gray-tan façade trimmed in white, with square windows and bold red doors. Wrought iron handrails frame the twin entrances. This sacred space was built by and for a community determined to worship freely.

Inside, stories live in the pews and pass through generations. George Liele, born into slavery in 1752 and later freed, founded this congregation, making it the oldest Black Baptist church in North America. His legacy endures in every hymn, every gathering, and every act of faith that shaped Savannah’s spiritual and literary landscape.

From sacred songs to silent monuments, Savannah’s stories endure. Next week, we’ll enter a tale where mystery deepens and Savannah becomes its most enigmatic character.

Attributions

Gwringle, CC BY-SA 3.0

Mattstone911, CC BY-SA 3.0

Leave a reply to Chloe Burer Cancel reply